Google has a long standing tradition of introducing changes to it’s search engine designed to enhance user experience, and Google’s dominance as a search provider essentially mandates the adoption of Google’s prescribed best practices. AMP promises to make the web faster, but embracing AMP might be more complicated than you would expect.

What is AMP?

Accelerated Mobile Pages (AMP) is a web content publishing format, developed by Google, which aims to improve user experience on mobile devices by optimizing webpages for performance. This is accomplished using a non-standard subset of HTML which provides only limited access to JavaScript and other native web technologies. The most common implementation of AMP is to use separate page templates for AMP, though this is not a requirement of AMP.

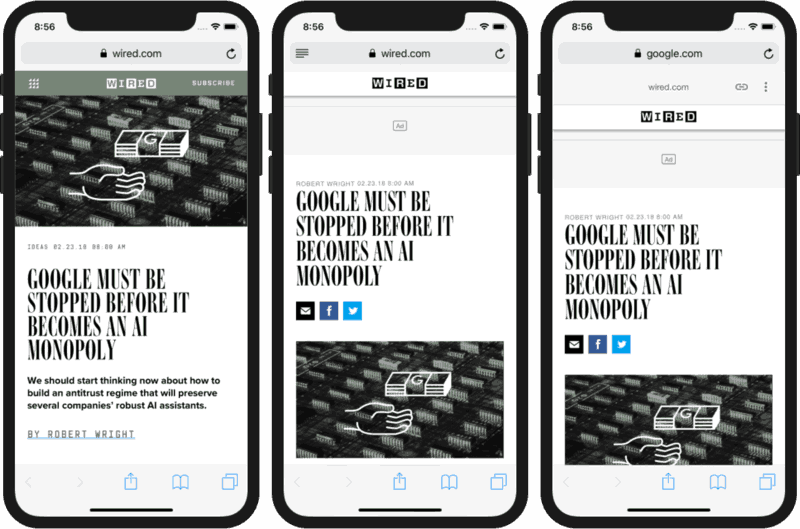

Here is a typical AMP setup:

- Original/Canonical URL: https://www.wired.com/story/google-artificial-intelligence-monopoly/

- AMP URL: https://www.wired.com/story/google-artificial-intelligence-monopoly/amp

- AMP Cache (Google)1: https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.wired.com/story/google-artificial-intelligence-monopoly/amp

Note: In May 2018 Google announced plans to incorporate new technology into AMP that would allow content creators to use their own URLs within Google’s cache.

Despite the fact that Google is primarily responsible for both the AMP format and an AMP cache implementation within Google search results, it is important to understand that the format and cache implementation are technically independent elements. Other platforms like Twitter and Cloudflare offer their own AMP cache implementations, but for the purposes of this article, “AMP” refers to Google’s AMP cache implementation.

AMP is a polarizing topic which has received widespread criticism from the web development community. Some of the criticism stems from the fact that Google has created a “closed” format which is not governed by an open standards organization; this allows the AMP team to move quickly, but does not create an inviting atmosphere for community involvement. Additional controversy is precipitated by Google’s use of their dominant market position to drive the adoption of the format by giving AMP pages preferential treatment within mobile search results. Furthermore, Google’s management of content served from the AMP cache, which retains users within Google’s own domain, has also fueled frustrations.

Why does AMP exist?

Colin Chapman, the founder of Lotus Cars had a famous philosophy: “simplify, then add lightness.“ He contended that while ”adding power makes you faster on the straights, subtracting weight makes you faster everywhere.” This is the lens through which we examine website performance—less is more.

Unfortunately, with ever-increasing pressure to drive results, website managers are driven to seek out any opportunity that claims to show a positive return on investment. With a multitude of providers each claiming that adding their service will improve conversion and provide more powerful user insights, content creators are easily convinced that adding more to their websites is the answer to their problems. In this way too, website managers can easily demonstrate progress to their supervisors. As these additions accumulate, site performance decreases, leading to an unpleasant user experience. By this point, the damage has been done—it’s difficult to justify getting rid of anything that’s claiming to produce a positive return on investment, even when those claims are difficult or impossible to substantiate. As it turns out, convincing content creators to add functionality to their website is easy, convincing them to remove functionality—which is generally a requirement of improving performance—is hard.

So here we are. While web practitioners have long been aware of the importance of site speed, incentives and penalties like Google’s Site Speed algorithm update (2010) did little to curb the ever-increasing size of webpages. Since that update, the average number of assets requested on a mobile webpage increased by over 140% (from 29 to 70). Over the same period, the size of the average mobile webpage increased over 725% (from 200KB to nearly 1700KB). Despite the fact that there is plenty of data which supports the idea that better page performance equates to more time onsite and increased conversion rates, most organizations have not defined a performance budget to educate decisions and protect site speed and user experience, so webpages grow larger while the user experience becomes slower.

By failing to improve performance, content creators are missing out on opportunities. Instead, tech giants introduced their own solutions which redistribute content with improved performance—Facebook (via Instant Articles), Google and Twitter (via AMP), and Apple (via the News app)—which allow them to keep users on their platforms longer, and make more money through their own advertising.

[T]he emphasis on speed… with things like Instant Articles, native is making the browser-based web look like a relic even just for publishing articles… [which] might pose a problem even for my overwhelmingly-text work. [My website’s] pages load fast, but the pages I link to often don’t. I worry that the inherent slowness of the web and ill-considered trend toward over-produced web design is going to start hurting traffic to [my site].

– Facebook Introduces Instant Articles by John Gruber

The depressing truth of why AMP exists is that Google gave the community a chance to make the web faster—we didn’t. Instead we broke another piece of the web. In it’s brilliance, AMP is a simplification masquerading as an enhancement.

Benefits of AMP

AMP’s biggest advantage is the restrictions it draws on how much stuff you can cram into a single page.

— How Fast Is AMP Really? by Tim Kadlec

Google has encouraged adoption of the AMP format by offering content creators increased readership through heightened visibility within search results. This occurs in a number of ways:

- A lightning bolt icon is displayed alongside AMP content within mobile search results.

- AMP content is eligible to be promoted into AMP carousels within mobile search results (including the “Top Stories” carousel which is prominently displayed).

- AMP content is cached by Google, served through it’s CDN, and preloaded within search results, allowing content to load “instantly”.

Speculation: Presumably the preferred placement in mobile search also impacts ranking in non-mobile search results, as Google announced that the “mobile index” would become the primary source of site rank in November 2016.

Criticisms of AMP

Critics of AMP believe that these benefits are an unfair anti competitive behavior due to the fact that non-AMP pages, which can be made to be faster than their AMP counterparts, do not get access to the same benefits as AMP pages. The result of preloading AMP content within search results is what allows AMP pages to load instantly; publishers can’t compete with that.

There is an axiom: “There is no right way to do the wrong thing.” I wonder now if the reverse is also true, or if Google has managed to do the right thing the wrong way. Google was able to leverage it’s search dominance to address performance in a way that no one else could, by offering business owners valuable incentives. However, because only AMP pages receive preferential treatment, only AMP pages are “instant”. Until business owners are convinced that overall performance is important, the web at large will continue to grow larger and load slower, which is the real problem that needs to be addressed.

AMP hasn’t solved the core problem; it has merely hidden it a little bit. … the incentives being placed on AMP content seem to be accomplishing exactly what you would think: they’re incentivizing AMP, not performance.

— How Fast Is AMP Really? by Tim Kadlec

In fact, even Malte Ubl, creator and tech lead of the AMP Project, has said “make AMP your own site.” The solution to addressing the problem of performance is to make your site faster, not to focus on AMP.

Content creators should also understand the trade-offs they are making when choosing to implement AMP. Unless content creators are willing to rebuild their existing websites, eliminating any functionality not supported by AMP, then publishers will need to assume the costs of creating and maintaining a second AMP version of each of their webpages. (Does this remind anyone else of m-dot mobile sites?) By using a closed format, and allowing Google to host their content, publishers are ceding control of their content to Google. Due to the nature of Google’s current AMP cache implementation, whereby AMP content is served from the google.com domain, publishers are accepting that their website (the content origin) may receive less traffic.

How does Google benefit from AMP?

Notice: This section contains speculation.

I don’t find it too hard to believe that Google can or will use AMP formatted content to fuel it’s AI initiatives. Scraping the web is a complicated business—enforcing a limited standard would allow Google to crawl and scrape content more easily, and use this data to power Google’s “Featured Snippets,” which are used to power the conversational UI of Google Assistant. Google confirmed that AMP links may be displayed in featured snippets of mobile search results in September 2017.

We also know that slow sites lead to fewer page views which lead to fewer ad impressions which results in fewer dollars in the pockets of ad platforms like Google. Google has a vested interest in maintaining a dominant position in digital advertising. In fact, the AMP format with all of it’s limitations on JavaScript and functionality, does support a variety of ads.

Of course, by writing the code for these new ad formats, [Google is] also putting itself in the middle of how those ads will be implemented, giving Google an ongoing place at the table for how the next generation of the mobile web will monetize.

Speed without AMP

As a parting thought for any reader who is considering implementing AMP, I’d like to share some wisdom from a very entertaining talk by Maciej Cegłowski called The Website Obesity Crisis which succinctly describes how to build a fast website:

Nutritionists used to be big on this concept of a food pyramid. I think we need one for the web, to remind ourselves of what a healthy site should look like. … Here is what I recommend for a balanced website …:

- A solid base of text worth reading, formatted with a healthy dose of markup.

- Some images, in moderation, to illustrate and punch up the visual design.

- A dollop of CSS.

- And then, very sparingly and only if you need it, JavaScript.

… my simple two-step secret to improving the performance of any website.

- Make sure that the most important elements of the page download and render first.

- Stop there.

-

To visit Google’s cached AMP page, you must be on a mobile device. ↩︎